La prestazione del cane da lavoro e il rapporto con il conduttore

Lefebvre et al. (2007) hanno studiato gli effetti della relazione tra cane e conduttore sulle prestazioni e sul benessere del soggetto. Per fare ciò hanno analizzato 303 questionari compilati da conduttori di cani dell’esercito belga, i cani erano in maggioranza pastori belgi malinois. Lo scopo principale del lavoro era determinare quanti conduttori dedicassero più tempo ed energia al proprio cane, portandoselo a casa (anziché lasciarlo nel canile della caserma) e/o praticando con sport ed attività cinofile indipendenti dalla vita militare (Lefebvre et al., 2007). Lo scopo secondario era individuare una relazione tra il maggior investimento sul cane (relazione e tempo trascorso insieme) e l’obbedienza, l’aggressività e il benessere (Lefebvre et al., 2007). I cani che vivevano in caserma, nelle pause tra i turni di lavoro, venivano alloggiati singolarmente in canile; i cani portati a casa a fine turno facevano vita libera con la famiglia del conduttore (Lefebvre et al., 2007). I questionari consegnati ai conduttori erano composti da 34 semplici domande che riguardavano la relazione tra il cane e il conduttore e la percezione che i conduttori avevano del comportamento e della personalità dei loro cani (Lefebvre et al., 2007). Tra le domande venivano chieste l’anzianità di servizio del conduttore, il sesso del cane, il sospetto se il cane fosse stato maltrattato o meno prima di essere arruolato nell’esercito e il tipo di relazione che si aveva con il cane (Lefebvre et al., 2007). Veniva poi chiesto che attività si praticavano con il cane nel tempo libero e dove viveva il cane che era portato a casa (in casa, in giardino, in un box ,eccetera). Molto importanti erano infine le domande sul comportamento del cane. Veniva chiesto se era socievole, se mostrava comportamenti aggressivi, se era obbediente e se aveva una personalità “equilibrata”, “aggressiva” o “timorosa” (Lefebvre et al., 2007). Infine, veniva indagata la presenza di anomalie comportamentali come il leccarsi le zampe, il distruggere oggetti, la presenza di diarrea, l’ululare, il camminare incessantemente, l’abbaiare o dare la caccia alla propria coda. Questi comportamenti dovevano essere osservati quando il cane stava nel box (Lefebvre et al., 2007).

143 conduttori (47.19%) portavano a casa il cane , o praticavano sport con lui; 49 conduttori (16.17%) lo portavano a casa e praticavano a sport con lui; 121 (39.93%) portavano a casa il cane. Queste scelte avevano più motivazioni: il 95.87% dei 121 conduttori che portava a casa il cane lo faceva per il suo benessere, mentre l’89.26% lo faceva per il rapporto che aveva con il cane (Lefebvre et al., 2007). Pochi conduttori lo facevano “perché era facile” (15.7%) e ancora meno al fine di ricevere l’indennità mensile di 75 euro (5.79%) (Lefebvre et al., 2007). 71 conduttori (23.43%) praticavano sport con il cane: il 54.93% attacco e difesa e il 43.66% ubbidienza. Altre discipline praticate erano jogging (22.54%), biathlon (16.90%), mondioring (11.27%), agility (8.45%) e/o R.C.I. (5.63%) (Lefebvre et al., 2007). Le motivazioni, nonché le successive scelte effettuate da chi portava a casa il cane, sembrano indicare un legame più profondo con l’animale. Già Podberscek e Serpell (1997) che avevano notato che coloro che passavano molto tempo in compagnia del cane, prendendosene cura, stabilivano con lui un legame più profondo.

Per quanto riguarda il comportamento del cane, è stata valutata l’obbedienza tramite la prontezza di esecuzione del comando “lascia”: 178 cani, ovvero il 58.75%, richiedevano al massimo tre ripetizioni del comando prima di lasciare, mentre 116 cani, ovvero il 38.28%, lasciavano dopo tre ripetizioni del comando o, addirittura, andavano separati fisicamente dal figurante. La percentuale dei cani ubbidienti era più alta tra quelli che venivano portati a casa (il 72.73% dei cani portati a casa ubbidiva entro tre ripetizioni del comando rispetto al 49.45% dei cani che vivevano in caserma) e tra quelli che praticavano sport (il 73.24% di quelli che praticavano sport contro il 54.11% di quelli che non lo praticavano) (Lefebvre et al., 2007).

Gli autori non hanno trovato alcuna correlazione tra l’anzianità di servizio del conduttore (e quindi la presunta esperienza cinofila) e l’ubbidienza, né legami tra presunti maltrattamenti subiti dai cani prima dell’arruolamento e livello di ubbidienza (Lefebvre et al., 2007).

Non è dato sapere con certezza se i cani più ubbidienti fossero stati portati a casa in virtù di questa caratteristica, o se l’ubbidienza sia stata migliorata dal maggior tempo trascorso insieme e dal praticare sport (Lefebvre et al.2007). La seconda ipotesi, tuttavia, sembra più probabile: Clark e Boyer (1993), infatti, hanno rilevato che l’ubbidienza aumentava se cane e proprietario passano più tempo insieme e se la relazione tra i due migliora. Anche Podberscek e Serpell (1997) e Kobelt et al. (2003) sono giunti a conclusioni simili, riscontrando un miglioramento dell’obbedienza e una riduzione dell’aggressività nei cani molto legati ai proprietari.

Il nesso tra aggressività e disobbedienza non è stato stabilito in maniera netta, ma Lefebvre et al. (2007) ipotizzano che, a monte, ci possano essere stati dei maltrattamenti. Essi, pur ritenendo necessari ulteriori approfondimenti, partono dal presupposto che una situazione di disagio vissuta dal cane possa trasformarsi in paura o aggressività. I maltrattamenti potrebbero quindi, per lo meno, nel caso di cani aggressivi, ridurre l’obbedienza del cane (Lefebvre et al., 2007). Del resto, altri studi hanno dimostrato che un addestramento basato su punizioni può compromettere il benessere del cane senza migliorarne l’ubbidienza (Hiby et al.2004; Schilder e Van der Borg, 2004).

Il 25.74% dei conduttori ha ammesso che il proprio cane ha morso almeno una persona. Il 19.83% dei cani portati a casa ha morso qualcuno, contro il 29.67% dei cani lasciati in canile Tra i cani che praticavano sport, il 19.72% ha morso e tra i cani che non praticavano sport il 27.71% (Lefebvre et al.,2007).

I conduttori potevano descrivere il cane come “equilibrato”, “timoroso” o “aggressivo”, scegliendo anche più di una di queste definizioni. La maggior parte dei conduttori (84.49%) ha definito il proprio cane “equilibrato”; l’11.22% “aggressivo” e l’8.58% “timoroso”. Non sono emerse correlazioni tra presunti maltrattamenti, equilibrio e aggressività, ma si è sospettato che il 58.82% dei “timorosi” fosse stato maltrattato. Per quanto riguarda l’obbedienza, il 59.55% degli equilibrati e il 42.31% dei paurosi erano ubbidienti, mentre il 79.41% degli aggressivi non lo era. La personalità del cane non è parsa avere alcun legame con il tipo di alloggio (casa del conduttore o caserma) né con la pratica di sport (Lefebvre et al., 2007).

Per quanto riguarda la socievolezza, il 67.99% dei cani era ritenuta essere socievole, il 24.2% poco socievole. Il 2.31% dei cani venivano invece descritti come più o meno socievoli a seconda del contesto. Il 77.69% dei cani portati a casa era ritenuto socievole, mentre tra quelli che rimanevano in caserma la percentuale scendeva al 61.54%. I cani socievoli erano anche più ubbidienti : il 63.59% dei cani socievoli era ubbidiente mentre lo era solo il 51.35% di quelli considerati poco socievoli. Il 63.64% dei cani portati a casa accettava di essere accarezzato da estranei, per i cani lasciati in canile la percentuale scendeva al 49.45%. I cani che accettavano di essere accarezzati da estranei erano anche più ubbidienti rispetto ai restanti soggetti: 61.68% contro 52.04%. La percentuale di conduttori che poteva avvicinarsi al cane, toccare il cane, o portare via la ciotola mentre il cane mangiava era più alta tra coloro che portavano il cane a casa: il 96.69% si poteva avvicinare; il 92.56% poteva toccare il cane e l’ 80.17% rimuovere la ciotola (le percentuali per i cani lasciati in canile diventavano rispettivamente 89.56% , 84.07% e 62.09%) (Levebre et al., 2007). In definitiva, i cani che vivevano a casa erano più socievoli, ma non si sa se siano stati portati a casa in virtù di questa caratteristica o se è stato lo stile di vita, caratterizzato da una maggiore interazione con gli esseri umani, a migliorare questa caratteristica, i ricercatori sembrano credere maggiormente in questa seconda ipotesi (Levebre et al., 2007). Non è emersa invece alcuna correlazione tra la pratica di uno sport e la socievolezza, ma gli autori sottolineano che questo potrebbe dipendere dal tipo di disciplina praticata, nella più parte dei casi si trattava di discipline di attacco e difesa (Lefebvre et al., 2007).

Tra i comportamenti inappropriati in canile, ritenuti indicatori di scarso benessere, i più frequenti sono stati: camminare avanti e indietro (22.11%), abbaiare (14.19%) e distruggere (11.55%). La percentuale dei comportamenti inappropriati cambiava a seconda dello stile di vita interessando il 7.14% dei cani che vivevano con i conduttori e l’ 11.07% di quelli che rimanevano in caserma. Il praticare sport si è rivelato molto importante: solo l’1.98% dei conduttori di cani che praticavano sport aveva notato questi comportamenti (Lefebvre et al., 2007). Vivere a casa con il conduttore e praticare sport hanno ridotto la presenza di questi comportamenti, studi simili, che vedevano protagonisti cani da compagnia, hanno individuato dei fattori che potrebbero aver portato a questi risultati. Kobelt et al. (2003) hanno scoperto, per esempio, che il tempo trascorso con il proprietario si correlava negativamente con anomalie comportamentali e Jagoe e Serpell (1996) hanno dimostrato che l’interazione con il cane e l’esercizio fisico riducevano l’aggressività.

Vi è piaciuto questo articolo? Se volete saperne di più date un’occhiata al PS. Non dimenticatevi di dare un’occhiata al Gundog Research Project!

Bibliografia:

Clark G.I e Boyer W.N. (1993). The effects of dog obedience training and behavioural counselling upon the human–canine relationship. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 37: 147–159.

Hiby E.F., Rooney N.J., Bradshaw J.W.S. (2004). Dog training methods: their use, effectiveness and interaction with behaviour and welfare. Animal Welfare, 13: 63-69.

Jagoe A., Serpell J. (1996). Owner characteristics and interactions and the prevalence of canine behaviour problems. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 47: 31–42.

Kobelt A.J., Hemsworth P.H., Barnett J.L., Coleman G.J. (2003). A survey of dog ownership in suburban Australia – conditions and behaviour problems. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 82: 137–148.

Lefebvre D., Diederich C., Delcourta M., Giffroy J.M. ( 2007). The quality of the relation between handler and military dogs influences efficiency and welfare of dogs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 104 (1–2): 49–60.

Podberscek A.L., Serpell J.A. (1997). Environmental influences on the expression of aggressive behaviour in English Cocker Spaniels. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 52: 215–227.

Schilder M.B.H. e Van der Borg J.A.M. (2004). Training dogs with help of the shock collar: short and long term behavioural effects. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 85: 319–334.

It is interesting that he points out that judges, in the UK, do not comment on the dog’s work (on the contrary, they are expected to so here) and that explaining what the dog did, in public… often leads the public to believe they know more than the judges. This proved to be true in my limited experience, watchers (Italian and foreign), despite being several hundred metres away from the dog, see – and foresee- mistakes that handlers and judges, despite being right above the dog “miss”! I thought, that people in the fifties were more considerate, but, apparently, the art of attributing inexistent faults to other handlers’ dogs has a long standing tradition.

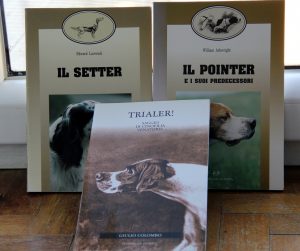

It is interesting that he points out that judges, in the UK, do not comment on the dog’s work (on the contrary, they are expected to so here) and that explaining what the dog did, in public… often leads the public to believe they know more than the judges. This proved to be true in my limited experience, watchers (Italian and foreign), despite being several hundred metres away from the dog, see – and foresee- mistakes that handlers and judges, despite being right above the dog “miss”! I thought, that people in the fifties were more considerate, but, apparently, the art of attributing inexistent faults to other handlers’ dogs has a long standing tradition. I would like to remember, however, that Giulio Colombo, besides breeding and judging, in 1950 published the book “ Trialer! An Essay on Gundogs” on Setters and Pointers. The book became a bestseller, it is still a bestseller indeed, and deeply influenced Italian breeders, judges and fanciers. Giulio Colombo ideal dog was a fast and furious super dog made of speed, deep castings and excellent nose. He called him “the pure”, “the fool”, then described him with these words: “The Trialer is the producer, the Masterpiece, the famous Artist’s painting, the fifty carats diamond, the pure gold”. He is New Year’s Day, not the remaining 364 days.”

I would like to remember, however, that Giulio Colombo, besides breeding and judging, in 1950 published the book “ Trialer! An Essay on Gundogs” on Setters and Pointers. The book became a bestseller, it is still a bestseller indeed, and deeply influenced Italian breeders, judges and fanciers. Giulio Colombo ideal dog was a fast and furious super dog made of speed, deep castings and excellent nose. He called him “the pure”, “the fool”, then described him with these words: “The Trialer is the producer, the Masterpiece, the famous Artist’s painting, the fifty carats diamond, the pure gold”. He is New Year’s Day, not the remaining 364 days.” Giulio Colombo, however, was skilled enough to see recognize good things at British trials, he admits, for instance, having seen some dogs he really liked. Yes, he says some dogs were “low quality”, but equally admits others were outstanding. I share his opinion: some British dogs lack of class, style and pace to compete successfully here but others… are absolutely not inferior to some Made in Italy dogs. I really, really liked some dogs I saw in Britain, and I am sure they would make our judges smile. Colombo mentions Seguntium Niblick, Pointer owned Mr. J. Alun Roberts who got first prize in All Aged Stake; Scotney Gary, Pointer owned by Mr. Arthur Rank, second prize; Scotney Solitaire, Pointer owned by Mr. Arthur Rank, third prize; Sulhamstead Basil d’Or Irish Setter, fourth prize; Ch. Downsmans Bracken, English Setter, fifth prize; Sulhamstead Nina d’Or, Irish Setter owned by Mrs. Nagle e Miss M. Clarcks and Flashaway Eve, English Setter owned by Col. A. S. Dalding. I think he really liked the Flashaway Eve as he describes him as very avid, stylish and very a typical low set gallop, he thinks he has all the features a dog needs to become a FT. Ch. He concludes with a note on Dero 4° del Trasimeno who was exported to the UK and is ones of the ancestors of Scotney Gary (and of some American dogs) and Blakfield Gide stepsister of the Italian Fast and Galf di S. Patrick. Author tanks those who made his experience possible: Mr. and Mrs Bank, Lady Auckland, Mr. Buckley, Mr. Binney, Mr. and Mrs. Mac Donald Daly, Mr. and Mrs. William Wiley, Mr. Lovel Clifford

Giulio Colombo, however, was skilled enough to see recognize good things at British trials, he admits, for instance, having seen some dogs he really liked. Yes, he says some dogs were “low quality”, but equally admits others were outstanding. I share his opinion: some British dogs lack of class, style and pace to compete successfully here but others… are absolutely not inferior to some Made in Italy dogs. I really, really liked some dogs I saw in Britain, and I am sure they would make our judges smile. Colombo mentions Seguntium Niblick, Pointer owned Mr. J. Alun Roberts who got first prize in All Aged Stake; Scotney Gary, Pointer owned by Mr. Arthur Rank, second prize; Scotney Solitaire, Pointer owned by Mr. Arthur Rank, third prize; Sulhamstead Basil d’Or Irish Setter, fourth prize; Ch. Downsmans Bracken, English Setter, fifth prize; Sulhamstead Nina d’Or, Irish Setter owned by Mrs. Nagle e Miss M. Clarcks and Flashaway Eve, English Setter owned by Col. A. S. Dalding. I think he really liked the Flashaway Eve as he describes him as very avid, stylish and very a typical low set gallop, he thinks he has all the features a dog needs to become a FT. Ch. He concludes with a note on Dero 4° del Trasimeno who was exported to the UK and is ones of the ancestors of Scotney Gary (and of some American dogs) and Blakfield Gide stepsister of the Italian Fast and Galf di S. Patrick. Author tanks those who made his experience possible: Mr. and Mrs Bank, Lady Auckland, Mr. Buckley, Mr. Binney, Mr. and Mrs. Mac Donald Daly, Mr. and Mrs. William Wiley, Mr. Lovel Clifford He then remembers why Setters and Pointers are supposed to work in a brace and to quarter in “good” wind while crossing their paths. Dogs should work in a brace to better explore the waste ground and, in doing so, they should work together, in harmony, like a team. Teamwork is very important, yet a dog must work independently from his brace mate and, at the same time, support his job and honour his points, these things shall be written in the genes. Dogs shall also be easy to handle so that they could be handled silently (not to disturb the quarry too much) and always be willing to cooperate with the handler. I don’t think I ever read these last two recommendations on any modern books on Setters and Pointers, have these traits lost importance?

He then remembers why Setters and Pointers are supposed to work in a brace and to quarter in “good” wind while crossing their paths. Dogs should work in a brace to better explore the waste ground and, in doing so, they should work together, in harmony, like a team. Teamwork is very important, yet a dog must work independently from his brace mate and, at the same time, support his job and honour his points, these things shall be written in the genes. Dogs shall also be easy to handle so that they could be handled silently (not to disturb the quarry too much) and always be willing to cooperate with the handler. I don’t think I ever read these last two recommendations on any modern books on Setters and Pointers, have these traits lost importance?