The English Springer by Arthur Croxton-Smith

From the book The Power of the Dog (1910)

THE ENGLISH SPRINGER

“O, how full of briers is this working-day world!”

Shakespeare—As You Like It.

“The chief requisite in all kinds of spaniels is,

that they be good finders, and have noses so true

that they will never overrun a scent. . . . .

They should be high-mettled, as regardless of

the severest weather as of the most punishing

cover, and ever ready to spring into the closest

thicket the moment a pointed finger gives the

command.”

General Hutchinson

The transition from the toy varieties to a spaniel is somewhat violent. The one is intended to please the eye, to gratify the æsthetic sense, and charm by his manners in the house; the other is designed primarily, by serving the sportsman in the held, to accomplish useful duties, but at the same time his docility of disposition, sagacity of expression and beauty of coat make him also a welcome companion when the day’s labours are ended. In estimating the worth of a gundog I should lay much stress upon his fitness for associating with mankind, for there is no doubt that if we win the confidence and friendship of our four-footed servitors the pleasure in their possession is much increased, and we have them under far better command when at work. Of all the foolish things written the hackneyed couplet so much quoted has precedence:

“A woman, a spaniel, and a walnut tree,

The more you beat them, the better they be.”

The ladies are quite capable of looking after themselves, and need no champion. I daresay a walnut tree may be all the better for a good “splashing,” as we used to say in the Midlands, but I am certain the less a whip is used on a dog of any sort the more likely are we to be successful in our efforts to exact prompt and ready obedience to our commands. The man who uses physical correction too freely is in want of a practical application of the monition contained in the Book of Proverbs: “A rod for the back of fools.”

Of the many handsome sub-varieties of spaniels with which we are familiar to-day the English Springer, perhaps, enjoys the least popularity, although his merits as a worker entitle him to a high place in our regard. As a show dog he has never assumed much prominence, but at held trials and on private shootings he is constantly demonstrating his utility. No other spaniel has been bred less for “points” or more consistently for work. Less excitable than the volatile Cocker, his longer legs and sturdier frame adapt him to purposes which the smaller is unable to perform. On the other hand, unless well broken, he, by ranging too far afield, may put up the game out of gunshot. It therefore follows that in his early days he must be made absolutely steady. Whether he becomes so or not is not so much attributable to the inherent wickedness of the dog as to the lack of patience in his breaker. One is almost inclined to say that the good breaker is born not made. At any rate, supposing you have the leisure, this is a task better undertaken by yourself than entrusted to a gamekeeper, who may have neither the time nor disposition to act as a wise schoolmaster.

A Springer is large enough to retrieve both far and feather, but whether or no he should be encouraged to do this depends upon circumstances. General Hutchinson says: “When a regular retriever can be constantly employed with spaniels, of course it will be unnecessary to make any of them fetch game (certainly never to lift anything which falls out of bounds), though all the team should be taught to ‘seek dead.’ This is the plan pursued by the Duke of Newcastle’s keepers, and obviously it is the soundest and easiest practice, for it must be always more or less difficult to make a spaniel keep within his usual hunting limits, who is occasionally encouraged to pursue wounded game, at his best pace, to a considerable distance.”

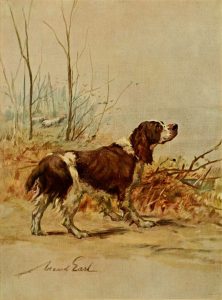

The word Springer is applied to all medium-legged spaniels, as apart from the short-legged ones, that are neither Clumbers nor Sussex. It is of good old English derivation, denoting the object for which the dog was employed—-to spring birds to the net or gun. The form of the dog has not undergone any marked change since a Dictionary of Sport, published shortly before Queen Victoria came to the throne, spoke of him as differing but little from the Setter, except in size, being nearly two-fifths less in height and strength. He is of symmetrical formation, varying a good deal in size from thirty pounds to sixty pounds, with unbounded energy. He may be a self-coloured liver, black, or yellow, or pied or mottled with white, tan, or both. Miss Earl’s picture brings out beautifully the correct shape of his body, and the handsome intelligent-looking head. Older pictures suggest that a hundred years ago or less the skull was broader between the ears, and the head shorter, but the refining process has not been carried far enough to jeopardise the brain power. In many breeds I have noticed that a broad skull indicates self-will and stubbornness, and therefore it seems to me that the slight change is all for the better.

The other variety of Springer indigenous to Wales is quite distinct from our own. He is smaller in size, and in colour he is red or orange and white, preference being given to the former.

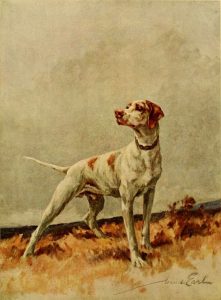

From the same book: click here to read about the English Pointer.