A few more words on gun shyness

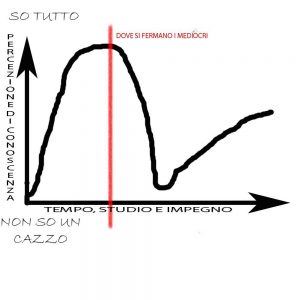

The previous article on gun shyness triggered many reactions. This had pretty much been forecasted, but I hoped to find a larger number of open minded people. In the end, however, I must admit hearing that you, owner, can be deemed responsible for your own dog gun shyness is not pleasant. Modern ethology is not being kind here, and it is much easier to blame the genes, the bitch, the stud or the breeder. Acknowledging the role of environment, upbringing and training is tough, it can make us feel guilty.

What did the readers say? I was told stuff like “I never introduced the pup to noises, but when the first day of the shooting season came, I brought him with me and shot a whole covey of partridge on his head and nothing happened! The dog is fine! Socialization and all that stuff, bullshit.” If these people had carefully read the first article, they would have realized I wrote that sometimes people are very lucky, and a dog can survive such intense experience, without any prior training. Is luck often that blind? Not really, what most likely happens is that the dog has been exposed to noise and other stimuli, the owner is simply not aware of this. Maybe the pups grew up by the house, or on a farm, where he learnt to recognize the tractor, the lawn mower and other sounds, maybe they were born during a stormy summer and learnt not to fear thunders. Dogs living near humans are generally exposed to noise and this could prevent gun shyness.

It is now time to discuss the second objection “In the past dogs were not socialized, nor exposed to noise, yet, they were normal”. This is a false myth. Let’s thing about the past: about one century ago, almost all the hunting dogs used to belong to rich people. These people had professional staff taking care of the dogs, it is highly unlikely that these dogs were poorly socialized. What about ordinary people? At a certain moment in history, people with lower incomes started to become interested in hunting dogs. These people were mainly farmers and, usually, had some mixed breed dogs who could work like a hound, a spaniel or a terrier (their contemporary equivalent would be the lurcher). These dogs used to live on the farm, close to their owner, to other humans and to human made noises.

In Italy, lower and middle class hunters began being involved with purebred hunting dogs after WWII, more vigorously from the sixties. At the time, the idea of breeding dogs as a business had not yet been developed and most of the litters were homemade and raised by amateurs. It could be the rich man with his staff or the plain hunter, sharing the burden of raising a litter with his wife and children: dogs and humans, whatever the wealth, used to live close to each other.

Things changed later, as soon as people realized that breeding and selling dogs could become a profitable business. Dogs began to be seen as “livestock” and raised as you would raise a farm animal. Separate living quarters with kennels were built and sometimes multiple litters were raised simultaneously. Pups are nowadays sometimes raised at a distance from human made noises and sometimes experience less interactions with humans. Commercial kennels, however, are not the only ones to blame, hunters have changed as well. Some hunters now live in the city, they do not want to share their apartment with muddy dogs and send them to live “in the countryside” (locked in kennels) paying someone local human being to go feed and clean them. Some hunters have a detached house in the suburbs, but pups destroy gardens so they end up in a kennel far from the house. Hunters return home late from work, they are tired and they do not feel like interacting with their new pup, even if he has a great pedigree and was paid a lot of money.

If the pup would not be such a thoroughbred but just a farm mutt, things could maybe be easier for him. Some modern purebreds are not that different from thoroughbred horses and are equally nervous and sensitive. We selected these dogs taking speed and reactivity in great account, well… they can now be highly reactive even when we would prefer them not to be. Times and contexts have changed, why people refuse to acknowledge this? I think we should pay more attention to the dogs’ needs and remember that the dog is “man best friend”. We should put the pup first and do our best to make him grow into a happy and fearless adult. We should no longer bring a gun shy pup back to the breeder asking for a replacement or a refund, we should, in a few words, be responsible of our actions.

PS. Don’t forget to take a look at the Gundog Research Project!

viamente, questa volta, sono scritti in italiano, per chi si lamentava della difficoltà del leggerli in inglese. Ci sarà anche una seconda parte sul numero di maggio.

viamente, questa volta, sono scritti in italiano, per chi si lamentava della difficoltà del leggerli in inglese. Ci sarà anche una seconda parte sul numero di maggio.