Quattro passi dentro casa: le cornici blu

Le cornici blu, come è giusto che sia, guardano dall’alto al

basso il telo cinese. Sono arrivate prima di lui, molto, molto prima. Ridendo e

scherzando, credo se ne stiano attaccate al muro da almeno una quindicina

d’anni. Sempre nella stessa posizione e sempre sopra la stessa pittura color

malva che mi ha reso inconfondibile tra i commessi del colorificio locale. Che

ci vada di persona, o che mandi l’imbianchino, il contenuto della latta non

deve essere rosa, ma non deve nemmeno essere viola. Guai a virare verso il

color lavanda, è troppo freddo, dobbiamo stare il quanto più vicini possibile

al color malva. Che poi è quasi sinonimo del color erica in fiore: dipende

dalla luce, tante cose dipendono dalla luce.

A proposito di colori freddi, non credo si vedrà mai una parete gialla

in questa casa, il color malva si abbia perfettamente al blu delle cornici. È

un blu che è tanti blu insieme: distalmente, così diciamo in anatomia, troviamo

un blu abisso, muovendoci verso l’interno, invece, abbiamo un azzurro chiaro

caraibico, commercialmente noto anche come “Bahamas Blue”. Le sfumature sono

interrotte da venature bianco azzurro. Descritte così, le mie cornici potrebbero

sembrare la seconda cinesata nel raggio di pochi centimetri: niente di più

falso, nell’insieme, l’effetto complessivo è piacevole.

Non posso dirvi dove le ho comprate, non perché debba

rimanere un segreto, semplicemente non me lo ricordo: ricordo di averle

comprate io, di questo ne conservo la certezza, ma ho dei buchi nella memria

simili a quelli di un gruviera. Credo provengano da una specie di brico locale,

uno di quelli che da un anno all’altro cambiano nome e proprietà, con

l’assortimento che, tuttavia, rimane all’incirca lo stesso. Però, potrebbero

anche provenire dal brico supremo, quello che sta a una ventina di chilometri

da qui e che non nomino perché mi mette troppa soggezione: è troppo lontano per

pensare di andarci. Ho visto gente rimettere a nuovo la casa durante queste

giornate di quarantena. C’è una casetta bianca, qualunque, lungo il tratto in

cui passeggio con i cani. In meno di un mese la sua recinzione è diventata più

nera, le sue persiane più verdi, e i suoi muri più bianchi. Se non si può

uscire di casa, da dove saranno arrivate tutta quella pittura e tutti quei

pennelli?

Comunque, tornando alle cornici blu, costoro sono un numero

di cinque, non ricordo esattamente il perché. Tre alloggiano stampe di

fotografie dell’inizio del secolo scorso , due invece delle copie di fotografie

in bianco e nero scattate negli anni ’70.

C’è però un incredibile trait d’union, tutte le immagini portano

dei setter inglesi. Prima di parlarvi delle immagini, devo parlarvi dei passpartout,

perché hanno una storia tutta loro. A comprare una cornice pronta ed infilarci

dentro una foto siamo capaci tutti, ci costa anche molto meno che far fare una

cornice su misura, il problema arriva quando gli abbinate ciò che dovrebbe contenere.

Le anime semplici si accontentano di far combaciare i bordi dell’immagine con

quelli della cornice: la gradevolezza del risultato lascia però molto a

desiderare. Tutti abbiamo almeno

un’immagine imprigionata in questa maniera, ma… ecco vi lascio i puntini di

sospensione, così potete decidere come pensarla.

La soluzione preferita da

pignoli-perfezionisti-ossessivi-compulsivi? Il passepartout della giusta

tonalità e della giusta misura. Ora che ci penso, perché il beige del

passpartout centrale è più crema degli altri, che danno invece sul corda? Chi

lo sa, ho impattato con l’ennesimo buco del gruviera. Nell’anno di nascita

delle cornici blu non esistevano ancora i tutorial su Youtube, però avrei

potuto aggrapparmi ai ricordi delle lezioni di educazione tecnica delle scuole

medie. Ci ho pensato, ma non ci ho neanche provato: è inutile cercare di fare

il salto dalla teoria alla pratica, se sai già che quanto allungherai la gamba

cadrai prima di toccare l’altra sponda.

Se esistesse una classifica del senso pratico, il mio sarebbe sotto lo zero. Con la manualità va un po’ meglio, ma sostanzialmente io sono quella che ha le idee, mi aspetto che siano gli altri a realizzarle. Le mie idee, ovviamente, sono ottime, solo difficili da mettere in pratica. È per questo che i commessi dei brico, i fabbri, gli imbianchini, i falegnami, insomma gli artigiani in genere, preferiscono non avermi come committente. Ricorrono a mille astuzie per non farsi trovare, ma nulla possono contro la mia determinazione. Mi evitano perché sanno di non poter essere scortesi: negli anni, infatti, ho elaborato un sistema di rottura di scatole raffinato ed efficace, nonché a prova di insulto. Perché se io rompo, usuro, consumo, trito…. ma in fondo sono educata e gentile, anche se vorrebbero tanto mandarmi a quel paese non ho fornito loro le munizioni per poterlo fare. In fondo sono persino buona: consapevole della mia totale assenza di senso pratico, affermo spesso che il mio coinquilino ideale sarebbe un caporeparto del Leroy Merlin.

Comunque, quando venne l’ora dei passepartout, la vittima

designata fu un anziano corniciao locale. Con poco entusiasmo, li realizzò, facendomeli

pagare a caro prezzo e poi narrò la vicenda al figlio che ereditò, insieme

all’attività, anche un atteggiamento sospetto nei miei confronti.

Ma arriviamo finalmente a raccontare cosa contengono le

cornici blu, partendo da quella più a sinistra. La prima cornice, vicino alla

finestra e a nord del televisore, contiene una delle due foto anni ’70. Una

setterina che sorveglia un cucciolo di circa tre settimane: l’età l’ho stimata

io.

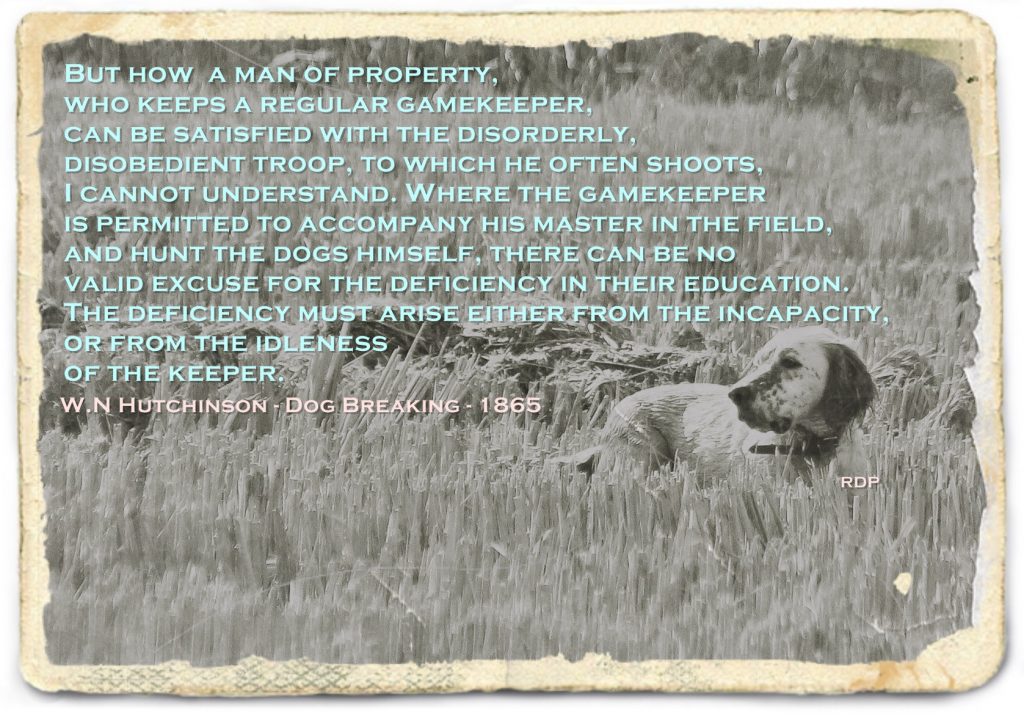

Con la seconda cornice abbiamo invece la prima foto di William Reid, un fotografo scozzese che risulta essere stato attivo tra il 1910 e il 1931. La “foto” è in realtà una pagina stampata proveniente da una qualche pubblicazione d’epoca. No Holt’s, no Christie’s: l’ho comprata su Ebay. Ora, io capisco il nazionalismo scozzese, capisco la sentita ricerca di identità da parte di questo popolo ma, intitolare l’immagine “Ready for the Call”, azzardatamente sottotitolata “A pack of Scottish Deerhounds on the Hills of the Vicinity of Edinburgh” (un branco di deerhound scozzesi sulle colline nei pressi di Edinburgo), mi pare un po’ tirato. Avete presente che cos’è un deerhound? Se non lo sapete ve lo spiego io: i deerhound sono dei levrieri specializzati nella caccia al cervo. La traduzione letterale del loro nome è segugi da cervo. Sono alti, molto alti sugli arti, smilzi, grigiastri e hanno un mantello duro, arruffato che spara in ogni direzione. Siccome so che è scortese paragonarli allo scopettone del wc, dirò che assomigliano a quelle spazzole irsute e avvitate che si usano per lavare l’interno delle bottiglie. Tolto il paragone politicamente scorretto, a me piacciono persino ma… non hanno nulla a vedere con le bestiole che appaiono nella foto. Abbiamo invece otto, forse nove – c’è una testolina che spunta dietro – cani. Di questi, quattro sono setter inglesi, tre sono pointer inglesi e uno sembra essere un cocker, per non sbagliare chiamiamolo semplicemente spaniel. I cani sono più o meno accovacciati e fermi, a dimostrazione che la steadiness (capacità di restare immobili), non è stata scoperta di recente dagli addestratori scozzesi. Dietro sembra vedersi un lago, più in là la sagoma dei moor.

Un lago fa da sfondo anche nell’immagine contenuta nella

cornice centrale, “A Young Game Keeper and His Nine Assistants, Aberfoyle

Scoltand” (un giovane guardiacaccia e i suoi nove aiutanti, Aberfoyle,

Scotland). Nove cani, anche qui, che scrutano l’orizzonte immobili in compagnia

di un guardiacaccia che indossa il tweed della riserva, come accade tutt’ora.

Bravo William! Good boy! Stavolta hai azzeccato il titolo.

In quarta posizione abbiamo “We are Seven” (siamo

sette), il cui sottotitolo è “A Scotch Lassie and her half dozen setter

puppies”. Lassie vuol dire ragazza, non vuol dire Lassie come lo intendiamo

noi. La razza “Lassie” non esiste, il cane a cui è stato dato quel nome, era un

cane da pastore di razza collie. Se siete arrivati fino a qui, e vi siete

persi, ci riprovo: quel cane protagonista di tanti film, era un collie di nome

“Lassie”, ovvero un cane da pastore di nome “Ragazza”. Se questo vi sembra

contorto, a me fa molto francese il contare i cani in mezze dozzine, sapete

come si dice 96 in francese vero? I cuccioli sono sei, con loro c’è una

ragazza, caso, o coincidenza, mi sento tanto io quando zampettavo per il

giardino urlando “Cagnoliniiiiiiii!”, “Cuccioliii” alla mia mezza dozzina.

La quinta cornice è sul confine con la libreria, cioè con una delle librerie, torniamo negli anni ’70, con una setter pensierosa, la stessa che fu mamma nella cornice iniziale. E il cerchio si chiude.

Se ti è piaciuto trovi il pezzo precedente qui e il successivo qui.