Wildlife Photographer of the Year a Milano

Alcuni anni fa, la biblioteca locale ha organizzato un corso di fotografia. Il docente, Bruno Valenti, un fotografo naturalista specializzato in rapaci notturne, trovandosi di fronte ad una classe molto eterogenea per competenze ed aspettative, ha impostato buona parte delle lezioni sul commento delle fotografie vincitrici (e segnalate) di questo concorso.

Il concorso fotografico Wildlife Photographer of the Year è organizzato dal Natural History Museum di Londra ma le opere premiate viaggiano poi in giro per il mondo per essere ammirate dagli appassionati. Al momento (fino al 10 dicembre 2017) le fotografie sono visibili a Milano: la mostra è organizzata da Radice Uno per Cento e ospitate dalla Fondazione Luciana Matalon a pochi passi dalla fermata MM1 Cairoli (linea rossa). Successivamente, la mostra si sposterà al Forte di Bard, in Val d’Aosta.

Dati e informazioni sulle opere finaliste sono presenti sul sito dell’ente organizzatore, evito pertanto di riscriverli, invitandovi a leggerle qui. Preferisco dedicare l’articolo a quelle che sono state le mie “impressioni” di giornalista e di fotografa amatoriale. Come qualcuno già sa, fotografo fin da bambina ma, per scelta personale, i miei soggetti preferiti sono i cani, non gli animali selvatici. Tuttavia, ammiro chi si dedica a questo tipo di fotografia pur dovendo tuttavia riconoscere che i “veri”, almeno per i miei parametri, fotografi di wildlife sono una minoranza di coloro che si ritengono tali. Fotografare animali selvatici dovrebbe significare fotografare selvatici veri, in natura (e non in pseudo parchi-safari per fotografi….) e, soprattutto, avvicinarsi a loro con grandissimo rispetto. Loro possono donarci immagini meravigliose, rispettarli è il minimo con cui li possiamo ricambiare.

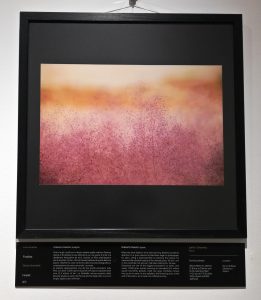

Altri due tasti dolenti, che spesso vanno a braccetto, sono quelli della ricerca dell’esotico ad ogni costo e dell’inseguimento dell’attrezzatura costosa. Molti sono convinti che per fare una bella fotografia sia necessario recarsi in capo al mondo e fotografare animali rarissimi: non è vero, e la giuria del Wildlife Photographer of the Year sembra darmi ragione. L’immagine simbolo della mostra è quella di una volpe che si aggira nei sobborghi di Bristol ma non è certo l’unico esempio di foto scattata dietro casa. La prima foto che si incontra nel percorso espositivo si intitola “The Moon and the Crow” e ha uno “scontatissimo” corvo come protagonista. Questa immagine è stata scattata nei dintorni di Londra dal sedicenne Gideon Knight che ha così vinto il premio Young Wildlife Photographer of the Year. Sarà che adoro fotografare la luna e le silhuettes prodotte dalla sua luce ma trovo questa immagine incredibilmente raffinata . “The Moon and the Crow” non è tuttavia l’unica immagine che vede protagonista le piccole cose che abbiamo tutti i giorni sotto il naso: nella categoria Piante e Funghi abbiamo l’italiano Valter Binotto che vince fotografando l’impollinazione di un nocciolo (Wind Composition) ma anche, della semplice erba fotografata con sapienza all’alba (Grass at Sunrise) dallo spagnolo Roberto Bueno. Se volete altri esempi di selvaggina della porta accanto, vi segnalo Refinery Refuge dello spagnolo Juan Jesús González Ahumada che si è “limitato” a fotografare un nido di cicogne ospite di una raffineria o… the Alley Cat dell’indiano Nayan Khanolkar, si tratta di un leopardo, non di un gatto, animale non tanto esotico per Mumbai dal momento che ne infesta le strade.

Le foto che ho citato possono essere ammirate, insieme a molte altre, sul sito del Natural History Museum ma, prima di chiudere, voglio ricordare anche Spiraling Sparrows di José Pesquero, Spagna, segnalata nella categoria “Impressioni”. L’immagine mi è subito sembrata famigliare, quello strano bokeh spiraleggiante era maledettamente tipico dell’Helios 44, una vecchia ottica analogica russa acquistabile a pochi euro, frecciatina dedicata a chi sostiene che per fare belle foto servano macchine costose e a coloro che, solo perché possiedono un corredo costoso si ritengono grandi fotografi.

I “veri” fotografi, in questo caso di wildlife, e la saggia giuria li hanno smentiti: l’attrezzatura conta, la tecnica conta, ma contano molto di più l’occhio, la capacità di giocare con la luce e la capacità di leggere il quotidiano alla luce della fantasia.

Ps. All’uscita della mostra ho acquistato il magnete della fotografia Nosy Neighbour ma probabilmente tornerò ad acquistare il catalogo (è disponibile anche su Amazon Wildlife Photographer of the Year Portfolio 26 ) che racconta la genesi di ogni immagine e ne descrive le caratteristiche tecniche.