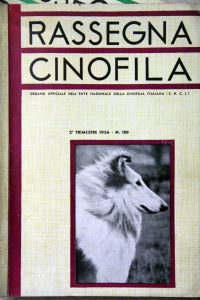

Come alcuni di voi già sanno, ho ereditato l’archivio del Dr. Ridella, veterinario e allevatore di setter con l’affisso Ticinensis. Mi sento onorata di essere stata scelta come custode di questi materiali, ma mi rincresce ammettere che ne ho ripulito e ordinato solo metà delle riviste. Tuttavia, circa 50 anni di editoria cino-venatoria, sono oggi ben archiviati e leggibili. Sapendo ciò, un amico mi ha chiesto di trovargli due articoli di Solaro del 1938 e del 1954 che, ovviamente, non sono riuscita ad individuare. Non dandomi per vinta, ho controllato anche gli anni limitrofi, niente da fare, ma ho trovato qualcosa di estremamente affascinante ed inatteso. Nel numero del secondo trimestre di Rassegna Cinofila (è l’antenato dei Nostri Cani) del 1956, c’è un bell’articolo di Giulio Colombo (1886-1966). Per chi non lo conoscesse, Colombo era allevatore con affisso della Baita, nonché un noto giudice. Aveva sempre cercato di tenere vivi i legami tra Italia e Gran Bretagna e l’Italia importando, tra gli altri i setter: Lingfield Mystic (vincitore del Derby inglese); Lingfield Ila, Lingfield Puma e Bratton Vanity.  Grazie all’articolo, ho scoperto che nel 1956, Colombo è andato a giudicare a Sutton Scotney (Hampshire – UK) e ha raccontato laesperienza. L’articolo è leggibile per intero nel PDF che potete scaricare qui o nella photogallery qui linkata. Ne riporterò però qui alcuni pezzi salienti.

Grazie all’articolo, ho scoperto che nel 1956, Colombo è andato a giudicare a Sutton Scotney (Hampshire – UK) e ha raccontato laesperienza. L’articolo è leggibile per intero nel PDF che potete scaricare qui o nella photogallery qui linkata. Ne riporterò però qui alcuni pezzi salienti.

Colombo comincia pensando a Laverack, Llewellin e Lady Auckland (che giudicava con lui) e con un excursus storico che spiega come mai setter e pointer siano stati selezionati in questa maniera. “Credo aver, inteso i due Grandi sussurrare a un dipresso così: Competizioni di giganti le nostre, quando ancora si credeva alla necessità del cane da ferma sul terreno della caccia, quando pointers e setters rispondevano al gusti venatori del cacciatore, quando non si codificava un bel niente a priori, teoricamente, per estetismi o postulati da tavolino senza aver vissuta o sofferta mai la, passione incontenibile dello sport codaiolo, fra le più strenue ed inebrianti passioni, quando pointers e setters, cani da Grande Cerca, si imposero selezionati perfezionati, secondo suggeriva la pratica diuturna di lunghe stagioni venatorie con l’esperienza del terreno e dei selvatico, a servizio del fucile vagante, e si stabilì la macchina animale perfetta, collaudata con formula aderente alla realtà per quel terreno e quel selvatico, e conquistò il mondo intero quella macchina intelligente, tanto che nati Inghilterra pointers e setters furon poi cittadini di ogni Paese.”

Non credo ci sia molto da aggiungere, poi continua con la descrizione dettagliata del lavoro che essi sono chiamati a fare: “II cacciatore ragionò così: di fronte a me la pianura sconfinata, ondeggiante di mammelloni di grani, di stoppie, di prati, di eriche, faticosa, lenta da per correre tutta scarpinando da coltivo a coltivo, da piaggia a piaggia in traccia delle compagnie di starne e grouses discoste le une dalle altre in famiglia ciascuna col proprio pascolo, e le lunghe pause senza incontri e senza sparare scoraggiano anche il cacciatore più caparbio: a me occorre un ausiliare speciale anzi una pariglia di tali, dall’olfatto possente, cerca indefessa. dalla ferma statica, dalla guidata corta, che a galoppo spinto per accorciare le distanze, nel tempo breve per la nostra passione da crepuscolo a crepuscolo, risparmiando a me ciechi e fortunosi passi, concludano spicci su grouses e su starne e magari su lepre sorniona; e perché io possa sparare a visuale libera senza tema, giù, a terra proni a frullo e schizzo. Drake e Dash, ed é il più bel momento della vita di cacciatore; e perché quel selvatico che non possono raggiungere né se vola né se galoppa, non induca in tentazione, proni testa fra gli arti ari in segno di rinuncia, voi cavalieri dei moors e praterie, per riporto e recupero i ho apparecchiato io stesso un valletto che non falla. il retriever, vi risparmi di strusciare il tartufo pistando, voi Signori », Torto o ragione, ragionavano cosi e così fu sempre categoricamente a quei tempi. Proscritti falsi allarmi di ferme senza presenza di selvatico, non si tolleravano inganni ed indugi oziosi, se Drake e Dash fermano ci sta il selvatico e non lo mollano più, e si raziocinava così: « Perchè noi si possa usufruire del lavoro di due cani, ed uno non costituisca il doppione dell’altro galoppandogli al fianco appaiato, li sguinzaglio nel bel mezzo dell’area da esplorare e partano essi uno verso destra e l’altro verso sinistra in senso opposto, e giunti a un centinaio di metri, anche di più a seconda del terreno vasto e sgombro, virino essi e ritornìno in direzione l’uno dell’altro, sempre nella scia dei vento, ma più oltre verso la meta lontana, in maniera da esplorare il terreno anche nel senso della direttiva di marcia, e si incontrino a metà cammino scambiandosi il lato come nella quadriglia dama e cavaliere, a ritmo cadenzato, con astuta sincronia e… nacque la cerca incrociata, non eleganza, ma accorgimento pratico.

E affinché l’intesa fra i due ausiliari fosse concorde, con rispetto della fatica e della autorità di ciascuno e l’uno approfittasse dei risultati concreti dell’altro, ecco che mentre l’uno dei cani bloccava col rito della ferma l’altro non persisteva ad esplorare, ma sostava immobile simulando a sua volta la ferma per mimetismo conscio e istintivo, per collaborazione atavica fra gli animali ida preda, e il segugio accorre scagnando all’indicazione sonora e Drake rispetta la ferma non sua ed ecco codificata la pratica del consenso, indispensabile con ausiliari che trescano veloci e lontani.

E siccome il selvatico tiene udito sensibilissimo, abolito ogni richiamo a voce o col fischio, cenni della mano al cane che di tanto in tanto sbircia al padrone per interpretarne le intenzioni, quindi tacita intesa fra cacciatore ed ausiliare, l’uno per l’altro. E quando s’ha da interrompere l’azione, un sibilo e i cani al terra, docili al guinzaglio e si inaugurò il drop e il down, non accademia da recinto, ma freno in terreno libero. Col tempo per emulazione fra scuderie, per sane rivalità sportive fra amatori di razze affini a chi tiene i l miglior cane con olfatto più potente a corsa più veloce e reazioni più pronte, nacque in un paese di scommesse, il cane da gara, il Trialler, via col vento, cane da Sport, ma riproduttore che rifornisca i ranghi per cacciare starne e grouses e non lepri e conigli, in terreno vasto e non negli scampoli di grano.”

Qui viene espresso in dettaglio il lavoro “ideale” dei cani inglesi e le motivazioni pratiche che stanno dietro a queste pretese. Leggendo questi paragrafi sento ancora più la mancanza delle mie esperienze britanniche, perché da loro le cose sono rimaste all’incirca come descritte qui. Se non avessi prima visto, e poi partecipato ai loro trials, sarei un cinofilo diverso, avrei un cane diverso ma… devo ammettere che sono contenta di quello che sono! Segue qualche notizia sulle regole del gioco, con riflessioni sui pro e sui contro delle diverse regole:“In Inghilterra non si redige relazione alcuna, non si concede qualifica, si comunica l’ordine di classifica dal primo ai quarto con una riserva, e stop, i concorrenti tanto intelligenti da valutare da sé gli errori dei propri allievi senza sentirseli ricordare per iscritto postumo dal Giudice e talmente sportivi da comprendere che se il Giudice ha creduto di disporre i cani in un dato ordine progressivo è ozioso recriminare e voler sostituire tante altre classifiche quanti concorrenti e spettatori, ognuna diversa dall’altra, ma tutte quante più oculate, più cognite, più probanti, più sapute, più pettegole di quella ufficiale!”

Non ci sta minuto di tolleranza, assurda nostrana indulgenza che consente al cane di dimostrare le proprie attitudini a far frullare, a rifiutare il consenso, a rincorrere, a beffare il conduttore, senza che il Giudice possa prenderne atto, coll’eventualità magari di non aver mai più durante il turno il cane occasione di ripetere quanto é suo costume perpetrare dì norma, e frodare magari un premio con relativa qualifica bugiarda.

Nemmeno si tiene conto di un lasso di tempo prestabilito per la prova: allorché il Giudice opina di essersi fatto un concetto probante del lavoro dei cani taglia corto, e su questo si potrebbe discutere, perché un minimo di percorso è più equo a garanzia delle probabilità comuni, eccetto per gli errori da squalifica. Vige il sistema dei richiami protratti con confronti ripetuti, con pericolo di dover sul finire della gara modificare da capo una classifica già plausibile”

Se volete saperne di più sulle differenze tra le prove italiane e quelle britanniche, potete andare a leggerle qui. Faccio una breve riflessione sull’abitudine inglese di non avere relazioni a fine prova: Colombo dice che il pubblico spesso tende a saperne di più del giudice. Persone che, pur stando a centinaia di metri dal cane, vedono e prevedono errori che sfuggono (secondo loro) ai giudici! Credevo che negli anni ’50 il pubblico fosse più , come dire, sobrio ma apparentemente l’arte di attribuire errori inesistenti ai cani degli altri ha radici antiche. Colombo poi racconta del Derby (non so se fosse identico all’attuale Puppy Derby, per soggetti sotto ai 2 anni) e non ho capito se i cani correvano a singolo o in coppia, siccome menziona poi le Brace Stakes (in coppia). “Nel complesso del lavoro nel Derby constatai qualche fase di dettaglio, insistenze su orme, qualche consenso stentato a comando, senza partecipazione né formale né conscia all’azione; Nota del Concorso presente in alcuni esemplari, ma frenata da frequenti incontri di fagiano, lepri e conigli, scarse le starne, e deplorevole il coniglio soprattutto, che conta é la starna, per fagiani basta il cocker. Punte in profondità. ritorni all’interno come in Coppa Europa, qualche intemperanza di richiami come da noi. Soggetti a corto di preparazione per il maltempo, alcuni veramente di classe, ma non superiore nel complesso alla nostra attuale. Primo Lenwade Wizard, pointer di Mr. Arthur Rank, di 15 mesi, stilista, corretto, galoppo sciolto, risolutivo sull’incontro. Secondo Lenwade Whisper, pointer di Messrs P. P. Wayre’s e G. F. Jolly’s, di 15 mesi, con buon percorso, benché lacets troppo compatti e qualche incertezza nell’indicazione.”

Seguono accenni alla Brace Stake: “Le Brace Stakes videro presenti due Setters, irlandesi, Sulhamstead Bey d’Or e F. T. Sulhamstead Basil d’Or. Basil soggetto rimarchevole, con reazioni pronte e buon olfatto, impegno e buon galoppo, qualche incertezza e ritorni all’interno, ferma e guida con espressione, consente, bene in mano, ben condotto, surclassa il compagno Bey e si aggiudica per proprio esclusivo merito il secondo premio, trattenuto il primo, della pariglia.”

Alla All Aged Stake era stato iscritto anche un weimaraner che poi non si è presentato. Colombo disquisisce sul far correre un continentale insieme a degli inglesi: “non avendo visto il Weimaraner sul lavoro non posso affermare se fosse o no nera Nota del Concorso dl Setters e Pointers, superflua qualsiasi meraviglia dal momento che corrono da noi diversi Kurzhaar ed Epagneuls perfettamente nella Nota della Grande Cerca assai più di qualche esponente di razza inglese; gli inglesi, con meno ipocrisia e più raziocinio, dal momento che alcuni continentali filano all’inglese, li fanno correre con gli inglesi; la Grande Cerca non è questione di coda lunga o corta, ma di garretti, olfatto reagendo, e non è escluso che un giorno i Continentali, italiani compresi, corrano a Grande Cerca, e pointers e setters a Cerca ristretta.”

Dopodiché tira le somme su quanto visto nel corso delle prove: “in Inghilterra la Grande Cerca non è più professata e sentita come un tempo, in un ambiente dove il cane da ferma è in crisi gravissima di impiego eccetto che alcuni pochi attivissimi Sportsmen fedeli alla formula antica; che è la prassi impiegata per correre la Grande Cerca che si allontana oggi in Inghilterra, o quantomeno a Sutton Scotney, non dal modello continentale ma da quello stesso descritto e commentato dagli Autori inglesi, praticato per il passato e introdotto poi sul continente: turni a singhiozzo, interruzioni di percorso per battere porzioni limitate, della pur vasta area, sfruttamento di appezzamenti, di scampoli di terreno percorribili in qualche minuto, assolutamente inidonei allo sviluppo della cerca in grande e anzi in contrasto con la cerca dinamica e veloce pertanto che nota personalità inglese ebbe a definire alcuni: turni da Springers; si tollerano dai conduttori troppe fasi di dettaglio e si ammettono lunghe guidate inespressive con schizzo finale di lepre e coniglio considerate valide, e niente sta ad attestare la possibilità di pistaggio che il Trialler naso al vento deve trascurare non essendo suo compito preoccuparsene; si dimentica spesso che il consenso è attivo, partecipante, solidale con il cane in ferma e non rinunciatario e passivo per obbedienza; non si reprimono sempre i ritorni all’interno e si tarpa talora l’azione del cane di lato costringendolo a percorso inadeguato allo scopo stesso della velocità.”

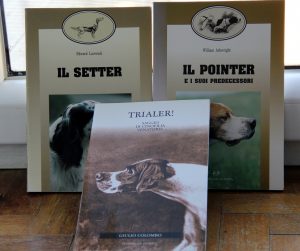

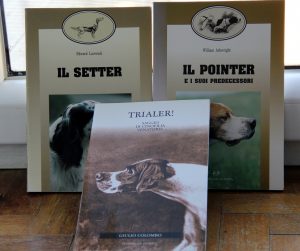

Il cane da ferma era in decadenza in Gran Bretagna nel 1956? Non lo so, non c’ero, quello che posso intuire da letture passate ed esperienze presenti è che la realtà venatoria britannica era (ed è) completamente diversa dalla nostra come potete leggere cliccando qui. La loro gestione faunistica-venatoria ha indubbiamente favorito spaniels e retrievers, a scapito dei cani da ferma. Probabilmente, nel 1956, i cani da ferma erano comunque cani di nicchia e in stagnazione, mentre da noi si assisteva ad una sorta di ascesa della caccia con il cane da ferma, gli inglesi in particolare. Innanzitutto la Grande Cerca intesa da Colombo nel 1956 era molto diversa dalla Grande Cerca attuale ma… gli inglesi hanno mai avuto una vera e propria Grande Cerca? Non ricordo nulla di specifico ad opera di autori inglesi. Non dico che non sia mai stata descritta, dico che non ne ho mai letto e mi piacerebbe leggerne su uno dei testi a cui fa riferimento Colombo, senza però indicarne i nomi. Mi piacerebbe poter conversare con lui e capire, capire cosa intendessero gli inglesi – secondo lui- per Grande Cerca e capire la sua visione. La sua visione, in fondo la conosciamo, non possiamo certo dimenticare che il cane ideale per Colombo era velocissimo, dalla cerca estrema, dal naso superlativo. Lo chiamava “il puro”, il “folle” e in “Trialer! Saggio di Cinofilia Venatoria” (1950) lo definiva: “Il Riproduttore, Il Capolavoro, il quadro d’Autore, il brillante di cinquanta grani, l’oro zecchino. E’ il Capodanno, non gli altri 364 giorni.” La cinofilia italiana è stata profondamente influenzata dalla visione di Colombo, ma non quella britannica e, come dicevo sopra, non sono nemmeno certa che inizialmente fosse indirizzata in quella direzione. [In ogni caso mi sono rimessa a leggere Arkwright a piccoli passi].

Turni da spaniel. Interruzioni di percorsi, terreni questionabili, lunghe fasi di dettaglio, lunghe guidate eccetera, le ho viste?Ni. Ho seguito e partecipato ad almeno 20 trials, forse di più, e ho visto alcune delle cose di cui racconta Colombo ma andava sempre così. Molto andava a discrezione dei giudici e dei guardiacaccia (è il guardiacaccia che ti dice dove puoi fare il turno!) e il livello dei cani era variegato. Non so come fosse la situazione a Sutton Stockney ma, in certi trials a grouse si corrono in mezzo a densità di selvatici impressionanti. Non è che si possano fare chissà quali percorsi. I consensi a comando? Li chiedono ancora anche se un consenso naturale è molto apprezzato e si sta lavorando in questo senso. Tirando le somme, comunque, credo che Giulio Colombo si aspettasse di assistere a qualcosa di diverso e sia rimasto un po’ spiazzato. Ciò nonostante, Colombo non era uno stupido e ammette egli stesso che anche un giudice britannico potrebbe non essere colpito sempre in positivo dai trials italiani: “Benchè una sola prova controllata da me non possa fornirmi indice probante del complesso di un materiale setter e pointer, esiguo come numero nei confronti dell’italiano e francese, da quella sola gara di Sutton Scotney (dovrei dedurne una netta decadenza rispetto alla nostra; mi guardo dal farlo: probabilmente un Giudice inglese avrebbe la stessa impressione da alcuni turni nostrani alla Cattanea, a Borgo d’Ale ed Alice Castello.”

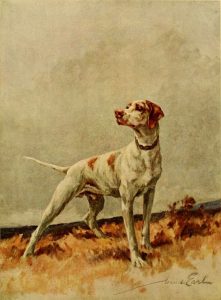

Il nostro inviato ammette altresì di aver visto, oltre a cani meno buoni, anche cani buoni: “Se alcuni concorrenti si palesarono tassativamente negativi al compito del Trialler, altri al limite quattro pointers almeno, due setters inglesi e un irlandese furono in tal classe da doverli rammaricare dal non poterli rivedere mai più. Fra i premiati Seguntium Niblick, pointer di Mr. J. Alun Roberts, di due anni, primo, velocissimo, sicuro sull’incontro, senso del selvatico. Scotney Gary, pointer di Mr. Arthur Rank, due anni, velocissimo, stilista, senso del selvatico, olfatto, secondo; Scotney Solitaire, pointer di Mr. Arthur Rank, di non ancora due anni, tutto nella Nota, testa alta, corretto, olfatto, reazioni, terzo; Sulhamstead Basil d’Or, irlandese, impegno, testa alta, corretto, quarto; Ch. Downsmans Bracken, setter inglese, dalle reazioni rapide, le ferme schiacciate slittando, lunghe e significative, infortunato su starne durante un rispetto di lepre, quinto. E lo indiavolato Sulhamstead Nina d’Or, setter irlandese di Mrs. Nagle’s e Miss M. Clarcks’s, di non ancora l’anno, partito su lepre, e quello inglesino blu belton dalla cerca ampia, avida, Flashaway Eve, del Col. A. S. Dalding’s, di non ancora due anni, che tende al fuori mano sul fianco, ma possiede tanta avidità e stile setter e galoppo radente da presagirne un Campione, se ben condotto.” Condivido appieno, la mia esperienza è identica alla sua: accanto a cani poco stilisti e lenti, ci sono soggetti che non sfigurerebbero anche alle nostre prove: in 60 anni è cambiato poco.

L’articolo di Colombo si chiude così: “Ma da Oltre Manica si importarono pointers e setters eccelsi, ma oltre Manica vige ancora sangue di Dero 4° del Trasimeno di Vignoli, sangue ricordato, vantato, e scorre nelle vene del secondo classificato, Scotney Gary, sangue che emigrò anche in America per ritornare in Inghilterra; e Blakfield Gide di Waldemar Marr, sorellastra di Fast, e Galf di S. Patrick di Nasturzio, sono citati in Inghilterra, paese per niente sciovinista, fra i migliori e più validi riproduttori, ed esponenti dei Pointer in quegli allevamenti: ricordiamolo anche noi.

Da “Rassegna “ ringrazio Mr. e Mrs Bank, Lady Auckland, il Segretario Generale del Kennel Club Inglese Mr. Buckley, Mr. Binney, Mr. e Mrs. Mac Donald Daly, Mr. e Mrs. William Wiley, Mr. Lovel Clifford mio valido interprete, che mi furon prodighi di ospitalità ed attenzioni durante il breve, ma denso soggiorno in- Inghilterra. Formulo il voto che la passione del Trialler non venga mai meno nella Patria Augusta del Signore l’Aria!” [Chi volesse leggerlo per intero può scaricarlo qui].

Ho deciso di parlare di questo articolo perché ritengo contenga dei punti chiave utili anche al lettore contemporaneo. Quali sono? Mi piace innanzitutto che apra con un excursus storico che spiega come si siano evolute le razze da ferma inglesi. Sono il frutto di particolari selvatici e di particolari terreni. Sono il frutto della caccia in quelle circostanze, circostanze che ne hanno plasmato il temperamento e codificato il metodo di lavoro. Prima che esistessero le prove, esisteva la caccia, esisteva il cacciatore che, a fronte di situazioni di caccia complesse, volevano tornare a casa con qualcosa nella cacciatora. Le circostanze hanno subito reso chiari quali fossero i tratti da selezionare e i comportamenti graditi, nonché tutto ciò che doveva essere considerato difetto. I cani andavano a caccia e poi, se bravi, venivano presentati anche alle prove. Un tempo era così anche in Italia e… vorrei fosse rimasto tale. Oggi abbiamo Campioni di Lavoro che non sono mai stati a caccia, che sono di proprietà (o persino condotti ed addestrati) da gente che non pratica attivamente la caccia con il cane da ferma, o che la pratica in contesti e su selvatici che si discostano da condizioni ideali e probanti. Questo porta anche a non comprendere alcuni regolamenti nati tanti anni fa, e a fare confusione su quali siano i comportamenti corretti da parte del cane, eppure costoro spesso si ritengono “esperti”.  Se rileggete le parole di Colombo vedrete quanto stima il fermo al frullo, il down e il drop, definendoli “non accademia da recinto, ma freno in terreno libero”, beh nella nostra penisola sono ancora abbastanza fraintesi. Non so se Colombo sia stato anche a trials su grouse ma la sottoscritta ha impiegato pochi minuti sul moor a capire che lì, questi insegnamenti sono indispensabili. Colombo ricorda anche l’importanza del percorso, del saper stare sul vento e del lavoro in coppia. Lavoro in coppia che deve essere armonico, di squadra facendo capo a caratteristiche che devono essere nella genetica del cane. I cani devono anche essere facili da condurre, collegati e disponibili a collaborare con la minima necessità di ordini sonori, o i selvatici sarebbero disturbati troppo. Questi appunti mancano in tanti libri di cinofilia venatoria moderna, hanno forse questi tratti perso importanza?

Se rileggete le parole di Colombo vedrete quanto stima il fermo al frullo, il down e il drop, definendoli “non accademia da recinto, ma freno in terreno libero”, beh nella nostra penisola sono ancora abbastanza fraintesi. Non so se Colombo sia stato anche a trials su grouse ma la sottoscritta ha impiegato pochi minuti sul moor a capire che lì, questi insegnamenti sono indispensabili. Colombo ricorda anche l’importanza del percorso, del saper stare sul vento e del lavoro in coppia. Lavoro in coppia che deve essere armonico, di squadra facendo capo a caratteristiche che devono essere nella genetica del cane. I cani devono anche essere facili da condurre, collegati e disponibili a collaborare con la minima necessità di ordini sonori, o i selvatici sarebbero disturbati troppo. Questi appunti mancano in tanti libri di cinofilia venatoria moderna, hanno forse questi tratti perso importanza?

Credo ora abbiate capito perché io ritenga il resoconto di Colombo su Sutton Scotney affascinante ed intrigante. Poi si aggiunge qualcosa di personale: proprio come lui, ho avuto modo di assistere (e prendere parte) ai British Trial e essi significano molto per me. Mi hanno trasformato in un cinofilo “diverso” e mi hanno consentito di avere un cane “diverso”.

Per saperne di più sulla cinofilia britannica cliccate qui.

Grazie all’articolo, ho scoperto che nel 1956, Colombo è andato a giudicare a Sutton Scotney (Hampshire – UK) e ha raccontato laesperienza. L’articolo è leggibile per intero nel

Grazie all’articolo, ho scoperto che nel 1956, Colombo è andato a giudicare a Sutton Scotney (Hampshire – UK) e ha raccontato laesperienza. L’articolo è leggibile per intero nel

Se rileggete le parole di Colombo vedrete quanto stima il fermo al frullo, il down e il drop, definendoli “non accademia da recinto, ma freno in terreno libero”, beh nella nostra penisola sono ancora abbastanza fraintesi. Non so se Colombo sia stato anche a trials su grouse ma la sottoscritta ha impiegato pochi minuti sul moor a capire che lì, questi insegnamenti sono indispensabili. Colombo ricorda anche l’importanza del percorso, del saper stare sul vento e del lavoro in coppia. Lavoro in coppia che deve essere armonico, di squadra facendo capo a caratteristiche che devono essere nella genetica del cane. I cani devono anche essere facili da condurre, collegati e disponibili a collaborare con la minima necessità di ordini sonori, o i selvatici sarebbero disturbati troppo. Questi appunti mancano in tanti libri di cinofilia venatoria moderna, hanno forse questi tratti perso importanza?

Se rileggete le parole di Colombo vedrete quanto stima il fermo al frullo, il down e il drop, definendoli “non accademia da recinto, ma freno in terreno libero”, beh nella nostra penisola sono ancora abbastanza fraintesi. Non so se Colombo sia stato anche a trials su grouse ma la sottoscritta ha impiegato pochi minuti sul moor a capire che lì, questi insegnamenti sono indispensabili. Colombo ricorda anche l’importanza del percorso, del saper stare sul vento e del lavoro in coppia. Lavoro in coppia che deve essere armonico, di squadra facendo capo a caratteristiche che devono essere nella genetica del cane. I cani devono anche essere facili da condurre, collegati e disponibili a collaborare con la minima necessità di ordini sonori, o i selvatici sarebbero disturbati troppo. Questi appunti mancano in tanti libri di cinofilia venatoria moderna, hanno forse questi tratti perso importanza?