A Gem from 1956: an Italian at British Trials

As some of you know, I inherited part of Dr. Ridella library and archive. Dr. Ridella was a veterinarian and an important English Setter breeder, his kennel name was Ticinensis. I feel really honoured to have been chosen as a custodian, but I hate to admit… I dusted and cleaned only half of the materials I have been given. Fifty years of canine magazines (1900-1950), however, are now readable and carefully stored. Knowing about this collection, a friend asked me to look for two peculiar articles written respectively in 1938 and in 1954. I could not find them but, while checking out nearby years, I found something absolutely unexpected, beautiful and fascinating. In the 1956 spring issue of the Rassegna Cinofila (the official name of the Italian Kennel Club Bulletin at the time), I found an article by judge Giulio Colombo (1886-1966).The man was a well known breeder (kennel della Baita) and judge for Setters and Pointers, he also imported some dogs from the UK and tried to keep the connection between Italy and Great Britain alive. Among his imports we shall remember Lingfield Mystic (who won the Derby); Lingfield Ila, Lingfield Puma and Bratton Vanity.

I discovered that, in 1956, he was asked to judge a partridge trial in Sutton Scotney (Hampshire – UK) and wrote about his experience. I am not going to translate the full article, I am just summarizing the most important points. (Those interested can see large pictures of the article here and download the .pdf file– which can be translated with google translator).

He opens his piece mentioning Laverack, Llewellin and Lady Auckland (with whom he was judging), and then explains how and why Setters and Pointers were created. He underlines that the game (grouse and grey partridges) and the waste, open and rough grounds forged these superlative breeds so that they could better suit the hunter. He tells us things I still see in the UK: Setters and Pointers are not expected to retrieve; Setters and Pointers must be very trainable and biddable, and that down and drop are fundamental teachings. Dogs must honour the bracemate and must quarter properly: Colombo explains the practical reasons behind all these expectations, this part occupies almost half of the article. His words make me miss what I saw, experienced and learnt during my time in the UK. As I often say, my dog would be very different if I had not seen their trials, and I would also be a much different trainer and handler. But I really like what I am now!!!

He then informs the reader about the differences (rules) between Italian and British trials: in Britain there is no “minute” (here all mistakes made during the first minute are forgiven); there is no established running time (here is 15 minutes) and good dogs are asked to run a second (and maybe a third round). He also lists the pros and cons of these choices. You can read more about the differences between Italian and UK trials in my older articles.  It is interesting that he points out that judges, in the UK, do not comment on the dog’s work (on the contrary, they are expected to so here) and that explaining what the dog did, in public… often leads the public to believe they know more than the judges. This proved to be true in my limited experience, watchers (Italian and foreign), despite being several hundred metres away from the dog, see – and foresee- mistakes that handlers and judges, despite being right above the dog “miss”! I thought, that people in the fifties were more considerate, but, apparently, the art of attributing inexistent faults to other handlers’ dogs has a long standing tradition.

It is interesting that he points out that judges, in the UK, do not comment on the dog’s work (on the contrary, they are expected to so here) and that explaining what the dog did, in public… often leads the public to believe they know more than the judges. This proved to be true in my limited experience, watchers (Italian and foreign), despite being several hundred metres away from the dog, see – and foresee- mistakes that handlers and judges, despite being right above the dog “miss”! I thought, that people in the fifties were more considerate, but, apparently, the art of attributing inexistent faults to other handlers’ dogs has a long standing tradition.

Colombo then describes what he saw during the “Derby”. I do not know if that Derby is like the current Puppy Derby (for dogs under 2 years, running in a brace) as I cannot understand whether the dogs were running alone or in a brace. He says he saw some back castings, some dogs who needed more training and some dogs who sniffed on the ground/detailed around the quarry too much. Rabbits, hare and pheasant further complicated things. First prize went to Lenwade Wizard, Pointer dog owned by Mr. Arthur Rank, 15 months old described as stylish, good gallop, good at handling birds; second prize Lenwade Whisper, Pointer dog owned by Messrs P. P. Wayre’s G. F. Jolly, aged 15 months. In the Brace Stake he noticed two Irish Setters Sulhamstead Bey d’Or and F. T. Sulhamstead Basil d’Or who eventually got second prize. As for the All Aged stake (which should be like the modern Open Stake), a Weimaraner was supposed to run with setters and pointers but was eventually withdrawn. Colombo was asked by Lady Hove to express his opinion: he seems to have had mixed feelings about what he saw. Let’s not forget that he later writes that pointing dogs are no longer common and popular in the UK, that people prefer spaniels and retrievers and Setters and Pointers are decaying. How are things now? Spaniels and retrievers still outnumber pointing dogs and this sounds a bit weird to Italians, being the average Italian hunter/shooter the owner of a pointing dog, most of often of an English Setter. But… the two realities are very different.

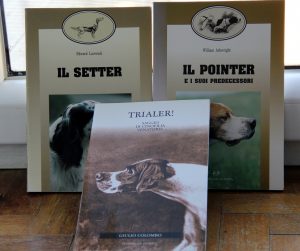

He writes that the “search” in the UK is no longer how it should be, and how it used to be. He states that, previously, the British wanted the dogs to run wider and faster. He says that that was the “ancient” way of interpreting the Grande Cerca. Whereas I read both Laverack and Arkwright, I do not recall anything like that and I am not familiar with other British authors advocating this working style. Also, I have not witnessed the Setter & Pointer early years, so I cannot say if what Colombo claims is true.  I would like to remember, however, that Giulio Colombo, besides breeding and judging, in 1950 published the book “ Trialer! An Essay on Gundogs” on Setters and Pointers. The book became a bestseller, it is still a bestseller indeed, and deeply influenced Italian breeders, judges and fanciers. Giulio Colombo ideal dog was a fast and furious super dog made of speed, deep castings and excellent nose. He called him “the pure”, “the fool”, then described him with these words: “The Trialer is the producer, the Masterpiece, the famous Artist’s painting, the fifty carats diamond, the pure gold”. He is New Year’s Day, not the remaining 364 days.”

I would like to remember, however, that Giulio Colombo, besides breeding and judging, in 1950 published the book “ Trialer! An Essay on Gundogs” on Setters and Pointers. The book became a bestseller, it is still a bestseller indeed, and deeply influenced Italian breeders, judges and fanciers. Giulio Colombo ideal dog was a fast and furious super dog made of speed, deep castings and excellent nose. He called him “the pure”, “the fool”, then described him with these words: “The Trialer is the producer, the Masterpiece, the famous Artist’s painting, the fifty carats diamond, the pure gold”. He is New Year’s Day, not the remaining 364 days.”

So, I really wonder whether any British authors had ever outlined such a dog, or whether Colombo just believed an hypothetical British author did or, again, whether he misunderstood some writings (he did not read English, as far as I know). So, basically, I think he was expecting something different and he did not entirely like what he saw. He complains about “interrupted” runs, short castings, slow runs, small parcels of ground to be explored, searches that gets “limited” by the judges and dogs forced to back on command. He writes that a British sportman defined some of the runs “Springer Spaniel work”. Some of these things still happens and might be even more noticeable if you come from Italy, where dogs are asked to run as much, as fast and as wide as they can (the pure, the fool…) and dogs usually back naturally but, our trials have other faults and he admits that, maybe, a British judge attending one of our trials, on a particular unlucky day, would not be impressed by what we show him.  Giulio Colombo, however, was skilled enough to see recognize good things at British trials, he admits, for instance, having seen some dogs he really liked. Yes, he says some dogs were “low quality”, but equally admits others were outstanding. I share his opinion: some British dogs lack of class, style and pace to compete successfully here but others… are absolutely not inferior to some Made in Italy dogs. I really, really liked some dogs I saw in Britain, and I am sure they would make our judges smile. Colombo mentions Seguntium Niblick, Pointer owned Mr. J. Alun Roberts who got first prize in All Aged Stake; Scotney Gary, Pointer owned by Mr. Arthur Rank, second prize; Scotney Solitaire, Pointer owned by Mr. Arthur Rank, third prize; Sulhamstead Basil d’Or Irish Setter, fourth prize; Ch. Downsmans Bracken, English Setter, fifth prize; Sulhamstead Nina d’Or, Irish Setter owned by Mrs. Nagle e Miss M. Clarcks and Flashaway Eve, English Setter owned by Col. A. S. Dalding. I think he really liked the Flashaway Eve as he describes him as very avid, stylish and very a typical low set gallop, he thinks he has all the features a dog needs to become a FT. Ch. He concludes with a note on Dero 4° del Trasimeno who was exported to the UK and is ones of the ancestors of Scotney Gary (and of some American dogs) and Blakfield Gide stepsister of the Italian Fast and Galf di S. Patrick. Author tanks those who made his experience possible: Mr. and Mrs Bank, Lady Auckland, Mr. Buckley, Mr. Binney, Mr. and Mrs. Mac Donald Daly, Mr. and Mrs. William Wiley, Mr. Lovel Clifford

Giulio Colombo, however, was skilled enough to see recognize good things at British trials, he admits, for instance, having seen some dogs he really liked. Yes, he says some dogs were “low quality”, but equally admits others were outstanding. I share his opinion: some British dogs lack of class, style and pace to compete successfully here but others… are absolutely not inferior to some Made in Italy dogs. I really, really liked some dogs I saw in Britain, and I am sure they would make our judges smile. Colombo mentions Seguntium Niblick, Pointer owned Mr. J. Alun Roberts who got first prize in All Aged Stake; Scotney Gary, Pointer owned by Mr. Arthur Rank, second prize; Scotney Solitaire, Pointer owned by Mr. Arthur Rank, third prize; Sulhamstead Basil d’Or Irish Setter, fourth prize; Ch. Downsmans Bracken, English Setter, fifth prize; Sulhamstead Nina d’Or, Irish Setter owned by Mrs. Nagle e Miss M. Clarcks and Flashaway Eve, English Setter owned by Col. A. S. Dalding. I think he really liked the Flashaway Eve as he describes him as very avid, stylish and very a typical low set gallop, he thinks he has all the features a dog needs to become a FT. Ch. He concludes with a note on Dero 4° del Trasimeno who was exported to the UK and is ones of the ancestors of Scotney Gary (and of some American dogs) and Blakfield Gide stepsister of the Italian Fast and Galf di S. Patrick. Author tanks those who made his experience possible: Mr. and Mrs Bank, Lady Auckland, Mr. Buckley, Mr. Binney, Mr. and Mrs. Mac Donald Daly, Mr. and Mrs. William Wiley, Mr. Lovel Clifford

So which are the key points for contemporary readers? Giulio Colombo outlines the Setter and Pointer history and explains why these dogs should work in a given manner. It is a matter of grounds and of birds: before trials ever existed, these dogs were hunting dogs and had to work all day long for the hunter who wanted to go home with a bag filled with birds. Setters and Pointers were tested in difficult and real hunting situations and it soon became clear which behaviours and attitudes were useful and which were not. The most sought after traits and behaviours were later coded and field trials were born, not viceversa. Dogs used to be tested during real shooting days and then, the best of them, were trialed. Things were like this during the early Pointer and Setter days and, in my opinion, they should not have changed. Nowadays, there are, at least in Italy, FT.Ch. who have never been shot over and, most of all, are trained, handled or owned by people who had never hunted, and never hunted on grounds and birds suitable for these breeds. People therefore do not understand some of field trial rules, nor how the dogs should behave but they consider themselves “experts”. Colombo mentions steadiness to flush and the commands down and drop, some of the most misunderstood things in my country. People think (and probably thought, already in 1956), that these commands are taught “just to show off”. On the contrary they can make shooting safer (a steady dog is not likely to be shot) and the drop and the down are extremely useful on open grounds. I am not sure whether Colombo attended grouse trials and, if so, how abundant grouse were but I took me only a couple of minutes to realize the importance of these teachings on a grouse moor.  He then remembers why Setters and Pointers are supposed to work in a brace and to quarter in “good” wind while crossing their paths. Dogs should work in a brace to better explore the waste ground and, in doing so, they should work together, in harmony, like a team. Teamwork is very important, yet a dog must work independently from his brace mate and, at the same time, support his job and honour his points, these things shall be written in the genes. Dogs shall also be easy to handle so that they could be handled silently (not to disturb the quarry too much) and always be willing to cooperate with the handler. I don’t think I ever read these last two recommendations on any modern books on Setters and Pointers, have these traits lost importance?

He then remembers why Setters and Pointers are supposed to work in a brace and to quarter in “good” wind while crossing their paths. Dogs should work in a brace to better explore the waste ground and, in doing so, they should work together, in harmony, like a team. Teamwork is very important, yet a dog must work independently from his brace mate and, at the same time, support his job and honour his points, these things shall be written in the genes. Dogs shall also be easy to handle so that they could be handled silently (not to disturb the quarry too much) and always be willing to cooperate with the handler. I don’t think I ever read these last two recommendations on any modern books on Setters and Pointers, have these traits lost importance?

I think you can now understand why I find Giulio Colombo’s report on Sutton Scotney intriguing and fascinating, but there is more, something personal: like the author, I had the privilege to watch and to take part in British trials, they mean a lot to me, I came back as a different “dog person” and they made me have a “different dog”.